“You’re back again, eh? You people remember us once in a year, come here, peep in our houses and disappear. It’s then just us and our suffering!” exclaims Asha of Mohaveerapatna, Ullal, mistaking team Coastal Mirror to be politicians. She is later told the visitors are journalists but pat comes her reply – “Ultimately, nothing has changed as far as our lives are concerned. Life’s still the same for us out here…”

And their life is, badly ‘hit’, every time the harsh sea waves do the trespassing and smash their dwelling. “Water comes into our house and we have to keep removing it every now and then. Should we cook food or should we keep cleaning our house?” she asks.

“Even if we cook food and keep, the sea waves take it away too along with them,” her neighbour Chitra joins in. “There have been instances where our ration card and other things inside the house got drenched due to the invading waves. Nothing is really safe in our little houses when these waves go berserk. But we cannot leave the sea and go away. Even if government gives us land, they will give it in some other area away from the sea which we don’t want. Our life is dependent on the sea and our income comes from fishing and related sea activities. We can’t go away from here” she adds.

Right next to Asha’s residence stand the ruins of Premakka’s house which fell prey to the monster waves about four years ago. For about a year or so, Premakka and her daughters had to manage in a little room attached to her husband’s ‘goodangadi’. That year, Premakka’s daughter Roopini, now studying BBM, was in tenth standard. “It was tough studying and preparing for SSLC exams in that makeshift house,” she recalls. Today, Premakka lives in another house nearby, constructed and gifted to her by Maruthi Yuvakara Mandali, a local organization. Did the government not step in and help her? “The Mandali didn’t bother knocking the government’s door. At the end of it all, the ones in trouble are given a thousand or two thousand rupees and the files keep moving from one table to another. So Mandali members didn’t bother going to them and built a house for this lady themselves,” says Ismail Podimonu, social worker.

“The CRZ authorities have laid out rules stating that houses constructed after 1991 in the restricted area, will not be entitled for any compensation and are considered illegal by them. The restricted area they say are divided into two zones – 0 to 200 meters which is the Zone A and the danger zone, and Zone B ranging from 200 to 500 meters. Ironically, the fish meal plant constructed on the Ullal coastline just recently, falls in that restricted zone. How come these industries got clearance from the authorities? Besides, the sea was far away from the current houses in 1991. How can they fix that year as the cut-off point?” Podimonu questions.

And the sea was indeed far away a few years ago. In those days, for many a family who live on the coastline of Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Uttara Kannada districts, their houses provided a typically beautiful ‘sea view’ which most people wish they had. Today, as they open their main doors, the same sea which once used to make a picturesque vista for them has turned into their nemesis, violently greeting them knocking right at their door. Contentment has paved way to irritation, for the uninvited guests that are the waves, keep storming into their houses. Not to mention the damage they have caused over the years.

“It was far far away. About 2-3 kilometers away from our house some 20 years ago,” recalls 70 year old Aminamma of Kotepura in Ullal. Today, she sees her little grandchildren being made to sleep in others’ houses and women in her own house sit together in one corner of a room to stay safe from the threat of the rampaging waves, which at times even smash the roof of their little dwelling. Young men on the other hand are busy keeping vigil at nights. “You never know. We live in constant fear and try to stay alert as much as we can, for the walls can collapse anytime,” says Abdul Ameen, Aminamma’s son.

62 year old Idinabba struggles as he walks along the boulders of the retaining walls laid across the coast to reach his residence. The monster waves hadn’t spared his family either. “Couple of years ago, the waves hit my house hard and a wall caved in, leaving one of my daughters with her leg injured as a result. She had to be hospitalised,” Idinabba recollects. Damaging walls notwithstanding, these waves create problems of a different kind as well. “They make our walls moist all the time and we keep getting electric shocks while trying to operate the electric switches,” he reveals.

The problem of sea erosion is not, however a simple nut to crack. It has its own complexities. “Sea erosion is a result of certain structural factors and certain weak points in the earth. Besides, this phenomenon is only seen in monsoon. The general perception is that sea erosion is caused by attack of storm waves hitting the beach. But there are certain other factors too that cause sea erosion, especially in our region. It is a wrong notion that the entire coastal stretch is prone to sea erosion. There are only some areas with certain geological aspects influencing the phenomenon. Sea erosions, especially in our coast, take place in areas where rivers meet the Arabian sea,” says Dr B M Ravindra, Deputy Director, Department of Mines and Geology, Government of Karnataka.

Dr Ravindra lays greater emphasis on the role of rivers in causing sea erosion in the region. “If you observe our coast and the areas that are normally affected by sea erosion, you will see small strips of land standing as a block between the river and the sea. During monsoon, excess water in these rivers also contributed by the waters that flow down from the Western Ghats, create pressure in the river channel. They do not get released into the Arabian Sea due to the strips of land blocking them (as in the case of Kotepura stretch and similar stretches in our coast) and have just a small opening or outlet for the river water to meet the sea. It’s like a little a bottleneck and immense amount of water inside the bottle that wants to flow out. Because of this blocking by the land strips, pressure is created in the river channel which is exerted on the land strip or the sandy alluvium, making it weak and vulnerable. Sand absorbs water and so does clay which lies beneath it. This weak strip of land, when encounters a harsh sea wave, invariably loses a chunk of land which the waves take away with them, which we call erosion,” Dr Ravindra explains.

He substantiates his point of rivers playing a role in the process by pointing out the areas prone to sea erosion in our coastal belt. “River Udyavara exerts pressure on coastal strips of areas from Udyavara to Kapu. River Pavanje and River Mulki play a role in sea ersion in areas of Sasihitlu and Mukka. Similarly, River Sita and River Swarna join the sea near Hoode and Bengre. So Hoode and Bengre areas are prone. Likewise, Sowparnika river exerts pressure on the thin strip of land at Maravanthe on which the National Highway is situated. In fact, it is just that piece of land that separates the sea from the river at Maravanthe, which is one of the majorly affected sea erosion areas. Every year the authorities have to do some circus to save the National Highway there from sea erosion,” he quips.

It is this aspect of the rivers playing a part in the erosion problem that makes Dr Ravindra and a few others have their own doubts of whether the proposal of building submersible sea walls will turn out to be a permanent solution or not. “By building a sea wall, they will be only taking care of the sea waves hitting the beach but the problem of rivers exerting pressure on the strips of land will remain. The problem will still be only partially solved. So I have my own doubts if this would succeed”, he says.

Dr S G Mayya, Department of Applied Mechanics and Hydraulics, National Institute of Technology - Karnataka, Surathkal, also has similar concerns. “At Ullal especially, there is a lot of circulation problem with respect to waves. By constructing a submersible sea wall, they will be blocking the waves alright but the measures they take to take care of orientation of waves are important. There has to be orientation in terms of waves around the breakwater, the coast and water coming out of the river mouth. Or else there are chances of waves getting diverted which will cause erosion at some other place. We cannot rule out the impact River Nethravathi has on erosion process at Ullal either. So a lot will depend on what they have planned to tackle this,” Prof. Mayya says.

Dr Subba Rao, an oceanology expert who has studied extensively the Mangalorean coasts, and also from the Department of Applied Mechanics and Hydraulics, National Institute of Technology - Karnataka, Surathkal, is quite positive about the project but maintains that much will depend on the way it is carried out. “It will reduce the waves hitting the shore considerably. But a lot will depend on the structure and the way it is constructed,” he says.

For Prof. Jayappa, Department of Marine Geology, Mangalore University, the greater concern is the durability of the seawall being built. “It will block the waves, no doubt. But it needs to be seen as to how long it will last. We will have to see since this is something new that is being implemented in our coast. But I feel shelling out 250 odd crores for just the Ullal stretch is a little too much” he opines.

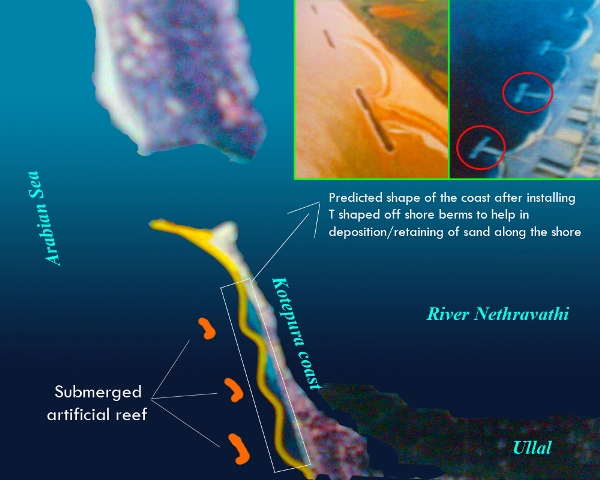

However, concerned authorities are confident that the submersible reef plan would succeed and the region will soon breathe easy as they see in it a permanent solution to the problem of sea erosion. The entire project has been divided into three phases. As part of the first phase, work will begin at Ullal’s waters and areas such as Sasihitlu, Hosabettu , Devbagh and Majali will be taken care of later on, phase-wise. The proposed plan of the submersible reef intends to cut the waves off at a distance away from the coast itself, thereby avoiding harsh waves from hitting the coast. Artificial reefs will be constructed which will be submersible i.e. under the water to block the strong waves at a distance of 600 meters away from the coast. This submersible sea wall will be around 38 meters long and 6 meters high from the sea bed. The sea wall’s foundation will comprise of geo textile material, which the authorities claim has the potential to withstand the harshest of sea waves. Another feature of this submersible sea wall would be the geo-tubes filled with sand which will be placed like bricks one above the other. The structure will be eco-friendly and cause no environmental harm and pollution, they say. Besides, four off-shore berms will be set up at the coast to help retain sand and prevent it from getting washed away and the nearby breakwater will also be altered a bit.

“Much thought and research has gone into bringing out this solution. Consultancy services were taken from ANZDEC, a company from New Zealand, who gave us this solution after having extensively studied the problem of erosion in our region and carrying out practical experiments with this model,” reveals A Srujan Rao, Assistant Executive Engineer, Department of Port and Inland Water Transport, Mangalore, who is one of the experts in the team formed for the sea wall project.

State minister for environment Krishna J Palemar who is also the district in-charge minister had announced earlier that a comprehensive project worth Rs 911 crore, with financial assistance from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has been formulated. However, as of now, an amount of about 250 crores has been earmarked for the first phase i.e. submersible seawall at Ullal. “This seawall will be the first of its kind to be built in the entire country. Apart from tacking the sea erosion menace, this submersible seawall will also facilitate fish breeding and help in fishing activities. Earlier, because of breakwaters, fishermen would encounter problems. But with this seawall, those problems would be solved,” says UT Khader, Ullal MLA.

However, the project has still not seen initiation thanks to the delay in the tender process. As many as four bidders including two Indian and two foreign firms had taken part in the pre-bidding meeting held recently. Of them, only one bidder has come forward. “With just one bidder, we are not content. We want a couple of bidders more for the tender,” says Shanth Kumar, Joint Director, Coastal Protection and Management Project, Department of Ports and Inland Water, Mangalore. MLA UT Khader on the other hand has said that concerned authorities will be urged to start the project even though just one bidder has knocked the door. “We will urge them to accept the one bid they have received so far and go ahead with the project. In my knowledge, it is a foreign company which is willing to work in collaboration with a Hyderabad company,” Khader reveals.

By September the tender has to be approved anyway, says Khader. Given that the work begins after rainy season this year, it will still take about 2 years to complete the entire project at Ullal which means that people who live dangerously at the coastline, will have to wait longer to breathe easy. Temporary arrangements will be made as usual this year too by the state government, laying boulders and creating temporary retaining walls to counter the troubling waves.

But until that submersible reef sees the light of the day, people of Ullal and other erosion prone areas will have to continue dreading the devil that is the deep blue sea. (courtesy: Coastal Mirror)

.

Comments

Add new comment