Washington D.C., Jul 21: The rediscovery of a lost planet could pave the way for the detection of a world within the habitable 'Goldilocks zone' in a distant solar system.

The planet, the size, and mass of Saturn with an orbit of 35 days is among hundreds of 'lost' worlds that University of Warwick astronomers are pioneering a new method to track down and characterise in the hope of finding cooler planets like those in our Solar System and even potentially habitable planets.

Reported in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the planet named NGTS-11b orbits a star 620 light-years away and is located five times closer to its sun than Earth is to our own.

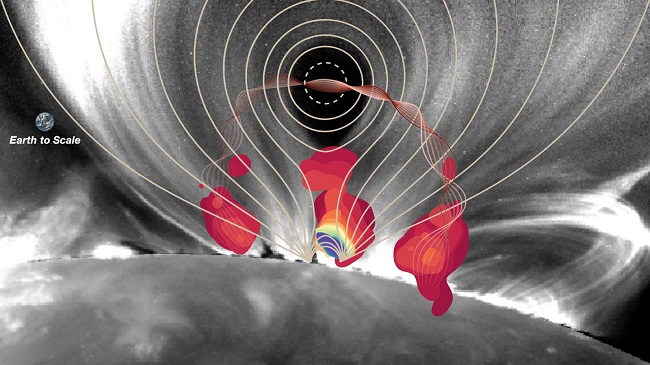

The planet was originally found in a search for planets in 2018 by the Warwick-led team using data from NASA's TESS telescope. This uses the transit method to spot planets, scanning for the telltale dip in light from the star that indicates that an object has passed between the telescope and the star. However, TESS only scans most sections of the sky for 27 days.

This means many of the longer period planets only transit once in the TESS data. And without a second observation the planet is effectively lost. The University of Warwick-led team followed up one of these 'lost' planets using the telescopes at the Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) in Chile and observed the star for seventy-nine nights, eventually catching the planet transiting for a second time nearly a year after the first detected transit.

"By chasing that second transit down we've found a longer period planet. It's the first of hopefully many such finds pushing to longer periods. These discoveries are rare but important since they allow us to find longer period planets than other astronomers are finding. Longer period planets are cooler, more like the planets in our own solar system," said Dr. Samuel Gill from the Department of Physics at the University of Warwick.

"NGTS-11b has a temperature of only 160°C -- cooler than Mercury and Venus. Although this is still too hot to support life as we know it, it is closer to the Goldilocks zone than many previously discovered planets which typically have temperatures above 1,000°C," added Gill.

The Goldilocks zone refers to a range of orbits that would allow a planet or moon to support liquid water: too close to its star and it will be too hot, but too far away and it will be too cold.

"This planet is out at a thirty-five days orbit, which is a much longer period than we usually find them. It is exciting to see the Goldilocks zone within our sights," said Co-author Dr. Daniel Bayliss from the University of Warwick.

"The original transit appeared just once in the TESS data, and it was our team's painstaking detective work that allowed us to find it again a year later with NGTS," said Co-author Professor Pete Wheatley from the University of Warwick.

"NGTS has twelve state-of-the-art telescopes, which means that we can monitor multiple stars for months on end, searching for lost planets. The dip in light from the transit is only 1 percent deep and occurs only once every 35 days, putting it out of reach of other telescopes," added Wheatley.

"There are hundreds of single transits detected by TESS that we will be monitoring using this method. This will allow us to discover cooler exoplanets of all sizes, including planets more like those in our own solar system. Some of these will be small rocky planets in the Goldilocks zone that are cool enough to host liquid water oceans and potentially extraterrestrial life," said Dr. Gill.

Comments

Add new comment